But doesn't the very implications of the statement already insinuate some kind of "inner-work", some sort of subliminal replacement of the system of signification for an economy of endlessly deferred signifiers? You weren't merely simply watching man's mastery over the optical in a re-presentation of the visual spectacles of nature: you were watching the rainbow itself, in all its exorcisms of nature. You were watching the new nature, the economy of the sign standing as "integral reality" (Baudrilliard). The plot, in the full throes of post-Great Depression optimism, heralds a bygone era of:

"sublime innocence and breathtaking artistry, at a time when its simple values rang true. In these cynical days when swashbucklers cannot be presented without an ironic subtext, this great 1938 film exists in an eternal summer of bravery and romance. We require no Freudian subtext, no revisionist analysis; it is enough that Robin wants to rob the rich, pay the poor and defend the Saxons not against all Normans, only the bad ones: "It's injustice I hate, not the Normans." (Robert Ebert, 2003, Chicago Sun-Times)

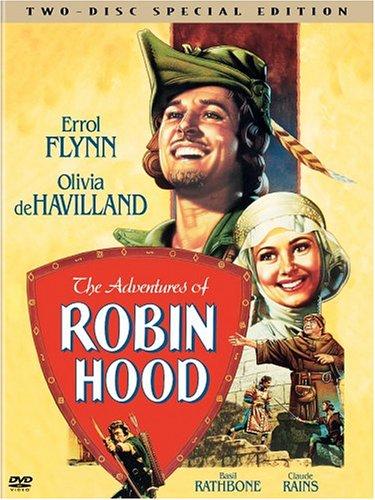

Guised through the battle between the Normans and the Saxons is a thin veil barely suggesting the triumph of Liberal Democracy over Fascism. Will Scarlett (played by Patrick Knowles) adopts a gender-queering role as Robin's (Errol Flynn) partner-in-crime, the youth adonis not quite conquered by the vestiges of sexuality, not fully mature enough to grasp the intricacies of the closet binary (Eve Sedgwick). Scarlett is knowingly cast in brilliant red (not simply a play on his name), trotting through the woods of green-ochre-and-brown Merry Men, sticking out like a visual sore-thumb, a bull's eye point on the target with an arrow tagged for the sexual, or communist deviant. It is Scarlett who appropriates the male Orpheus stereotype, bewitching the battle of Robin Hood and Little John with the sensuous strummings of his lyre. Unlike real men, Scarlett cannot fight: he sits, ousted from the orbit of homosociality in the other men's Hegelian master/slave fight for recognition, while knowingly understanding that he is a force of repulsion that keeps their economy in centripetal orbit.

But the main mystery belongs to Maid Mirian (Olivia de Havilland), forever sutured to the self-negating soaring orchestral strings of Korngold's richly-imagined score. Mirian's theme persists only within the community of the (fascist) Normands; like Scarlett, Mirian is subjectively desexualized, though continuously cast as a regelia of sexual desire - her sexuality has outrun her own sex. In a crucial turning point, Mirian "opens her eyes" (aided by Robin) to the deplorable conditions of the working class, "taxed" beyond their abilities to sustain her hedonistic upper-string wails. Only then can Mirian, as a self-determining woman, consider the advances of the vagrant "outlaw" as primal and possible: shattering the master-signifier of the Normands, Mirian's Symbolic world shatters in her "second death" only to find Robin as the only possible crutch. Zizek was right: in a world of reversals and outlaws, "evil" transgressions can only be accorded by a prior "ultimate" form of transgressive evil itself: The Law (of the Normands).

The complete and utter fragmentation of Mirian's Symbolic Universe de-sutures her from Korngold's score - she has no "place" in the Symbolic economy of signification, since her renunciation of beliefs exiles her from that position of privilege, de facto. Shedding the "master-signifier", Korngold's score (like a Peter-Pan shadow) unstiches itself from Mirian's body and unleashes a trap-door beneath her feet by way of falling out - Mirian is now the liminal being, left to reconstruct a universe of meaning based upon a Robin Hood as a new Sinthome. But her new self-determination contains a peverse narcissistic secret: impassioned as she is from breaking out of her initial blindness, it is the fantasmic desire of Robin Hood that sustains her entire being: fulfillment would surely close the impossible gap. Therefore, by saving Robin's life, Mirian's "love theme" returns, but it is not she that is signified, she becomes her own signifier, propelling the music, as it were, by her own will. This is the secret to Mirian's peverse statement to Robin as he climbs through the windows of her castle and proclaims he loves her. She simply replies "I don't love you." Of course she doesn't. She loves herself.

No comments:

Post a Comment