In a recent article on Music, torture and Repair, Suzanne G. Cusik asks the perennial Gordian question that keeps scholars' heads a turning: "but is this musicology?" She replies firmly "no", but always working on the margins of disciplinary standards and means. The more my eyes skim devotional texts, architecture, manuscripts and artefacts of the 12th and 13th century, this single barb - not unlike Bruce Holsinger's torturouos neumes that "pick" and penetrate the flesh - digs deep into my own disciplinary concerns. "But is this musicology," I ask myself, wondering where the wonderful permutations of Sirenhood and medieval music-making off the page may somehow effect a clausula, that is, a "turn" in my own musical thinking, leading me back to aesthetically privileged realms of "the music itself".

Indeed perusing the "Other" of musicology, its sister faculties of embodiment (such as Gothic cathedrals, manuals, treatises and art) tend to interpallate my own desirous tendencies to wander off interconnected pathways, delving into cultural issues that give "flesh" to abstract formulations which tend to exist freeze-dried in the many mausoleums of medieval scholarship. But ignoring these modes of embodiment, these marginal issues that trouble the dividing lines between pure signifiers and menstrually-charged ones (as in the case of much feminist discourse) tends to emphasize an unfair advantage to textuality, marking the point of phonocentric decline. I am not, as Derrida might warn, suggesting a return to an epistemology of orality which privileges the phonocentric as a marker of cultural presence, but bearing in mind the ways in which the "extra-textual" precisely figures medieval or contemporary notions of music and musicality.

Echoing Carolyn Abbate, one should not attempt to continue driving a hard-and-fast barrier between doxis and praxis. Rather, one should be wary of how such distinctions are brought to bear on material practices by their very modes of embodiment, indeed how they are located (in all senses of the word) as mediated objects. The contested nature of the "book" in the 12th century Medieval "renaissance" (for lack of a better descriptive) articulates a mode of embodiment, a Darstellung if you like, in a culture caught between orality, literacy and multilingualism. Similarly, preserving (or inscribing) neumes onto a page tends to eclipse the actual process of decoding these neumes in performance, reading, or decoration. The material culture of these books, these media, demands a closer investigation into means of embodiment, and the fashioning of the Medieval (performative) body.

In discussions of musica falsa, for example, these very practices which were deemed vagrant in ecclesiastical liturgy cannot simply be lifted off a post-19th century romanticized conceptualization of the autonomous "score" as a placeholder or trace of some metaphysical Platonic essence, wafting amids the fronds of our historically-tainted imaginations. Indeed such a valorization of the written (the inscribed) is to forget that inscription was a somatic gesture that facilitated memory and recall (as suggested by Carruthers), and somewhat constitutes a case of auditory blindness that simply extrapolates what was "notated" back into that same, safe conceptual sphere of "music" that jostles with the like of Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin. Even as these neumes provided visual "hooks" with which to drag the sonic out of the orifices of memory (and out through another orifice, the mouth), we should be careful not to allow the mere "visual" to "sing" all on its own, for the imagined bodies we pump its logic through are none other than our own contemporary bodies, fastidiously fashioned by years of listening and acculturation. The neumes - the word - performs precisely what Medieval writers were wary about: postlapsarian corruption.

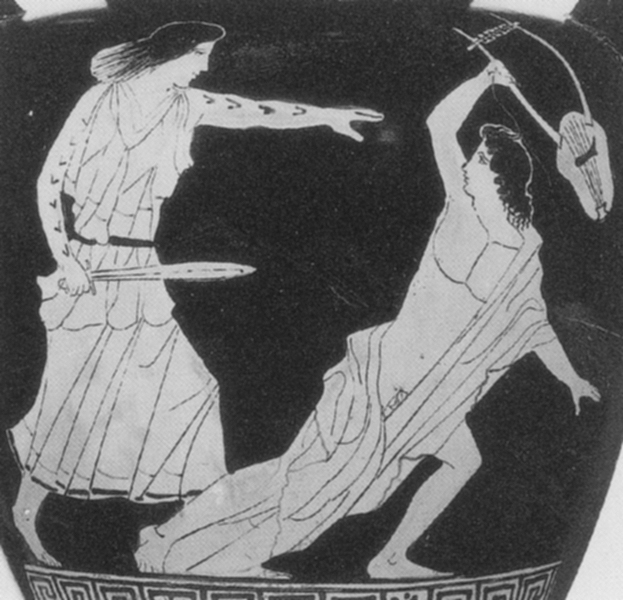

What bodies, then, should we accord these tracks? Imagining such vocalic bodies would be an excavatory task, albeit one frought with possible misinterpretation, crass assumptions and erroneous conclusions. But better give these voices flesh, I say, than recourse to yet another act of scholastic disembodiment. Perhaps it turns out that contemporary emphases on the empirical, that is, the systematic and notated, is but a fetishistic "blinding" of our scholastic condition to Orpheus's post-Bacchic condition. We choose to listen to the sweet, systematized and logical products of his severed head, while wearing dark glasses that filter out the horrific sight of his fragmented body. What unfathomable, abject secrets may lurk in the squirming entrails of Orpheus's horrific site of vocalic production becomes what Julia Kristeva calls the "semiotic", that pre-Oedipal choratic space of diffraction which contorts the health and safetly of our sanitized sanctuary of "the music itself".

Neither is the task to re-suture Orpheus' body to reflect our fantasies of normative sites of production. Indeed the journey at hand is to queer our eyes and ears not by backstepping to the authorial word, but by seeing with our eyes: reconstruing a sonograph of voice-body relations based on the already-queer features of the voice which functions simultaneously as a crutch of identification, and a "lost object", or what Lacan calls the objet petit a. By uncovering our own fantasies of voice-body suturing through an investigation of the "queer" medieval voice, I suggest that this may throw into relief our assumptions about the operation of music in culture and as a somatic artefact with destabalising ontological concerns. Vocalic body where voices mark the flesh and flesh taints the voice is charged empirical proof of our intrinsically "queer" features. One may imagine these "sewing surfaces" (or, as Zizek puts is, pointe de capiton) as cinemas which structure our phenomenal encounter with the world by masking an ontological lack or "gap" which forever threatens to throw the conceptual and the experiential out of joint. That is, a fundamental lack which threatens to sever our bodies and steal our voices, once and for all.

No comments:

Post a Comment